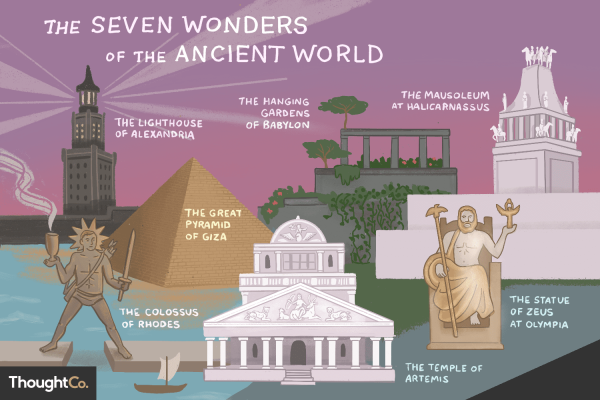

Often when it comes to discussions of art, we like to think of the greats: Well-renowned artists from Renaissance Italy, brilliant musicians from Germany and Austria, as well as intelligent thinkers and fantastic photographers. People often like to look back at the past and praise the works of the dead. Modern-day love of the past and its art goes back even further than that—all the way back to ancient antiquity, praising such works as the seven wonders of the ancient world, great philosophers like Plato, his student Aristotle, and even mathematicians like Pythogreas and Archimedes.

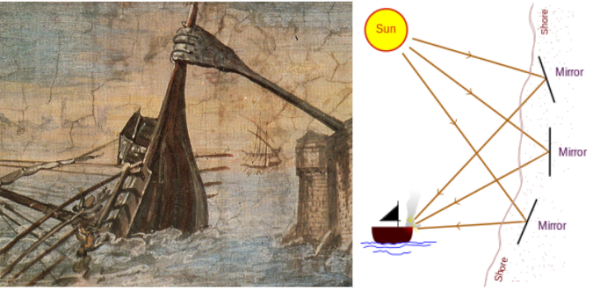

Many great minds of the past were extremely dedicated to their craft and the pursuit of knowledge. It is believed when Romans finished their two year siege of the town of Syracuse, persevering through Archimedes’ death traps including a massive claw that would wreck Roman ships, and a literal heat ray, Roman soldiers entered Archimedes’s room and found him studying circles in the sand. Even at the point of a sword, and threat of death, his last words were said to be “do not disturb my circles.”

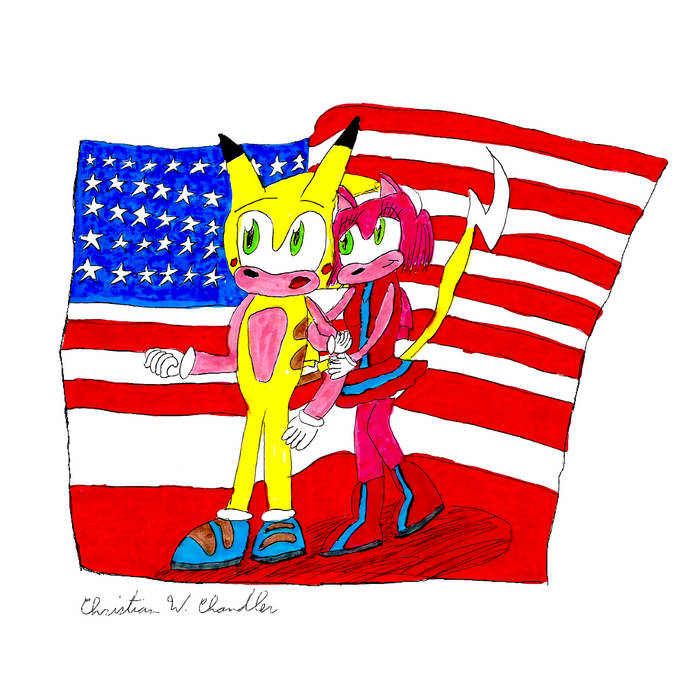

This event would then go on to inspire the 17th century painting by Luca Giordano titled The Death of Archimedes. Many lament and grieve the death of these great thinkers, the fall of great nations and their art. These traditionalists cling to antiquity even though the rest of the world has moved on, while others create new works while traditionalists prefer the past. If you ask one of these admirers of dead men why the great minds of yester-year are so important, they will bring up many reasons to praise the works of the past. When asked why we should praise works of the past, these people might say that there is a meaning behind these pieces of art, they spark further thinking and analysis, they cannot be fully enjoyed without reading between the lines.

Some of these same people will then go on to condemn modern art, stick their nose up at some of the movies, songs, or photographs of today, often calling them disgusting, gross, or unworthy of analysis. And while it may be understandable to have a knee-jerk reaction and stick one’s nose up at something disgusting, I believe it’s important to grit your teeth and bear it, endure the “stench” of filthy art, and see if there is something important it may be saying, some deeper emotion to unlock.

More often than not, there is a message beneath the surface: an idea, story, or experience equally as important and beautiful as those passed down by Plato, Michelangelo, Beethoven and other great minds of the past. To quote video essayist Jacob Geller “It is absolutely impressive when an artist spends huge amounts of time perfecting an intricate style, but that’s not why I experience them how I do. Feeling art, getting the [emotional experience of art] doesn’t hinge on me knowing how hard it was to create, it’s something that happens almost involuntarily.”

The intention of creating art is to provide an emotional reaction or experience, then why do people with authoritarian and close-minded thinking, such as the Nazis, immediately dismiss “filthy” or “gross” art, and purge it from the public’s view? I think it’s mostly because “degenerate” art requires deeper thinking, and can provoke deeper questions and thinking about the society it was created in, when on the other hand authoritarians prefer everyone to fall in line and follow a strict mold. So please, instead of immediately rejecting something that seems complicated or “disgusting” take a minute and engage with it, sometimes there is a diamond in the rough.

But first, I think it’s important to see how and why authoritarians, specifically the Nazis, might go about censoring and removing “Entartete Kunst” (German for degenerate art), and also the benefits of analyzing degenerate art.

Understanding “Entartete Kunst”

The first immediate explanation one might expect from a narrow-minded person is a very simple one: “simply because it is dirty and worthless,” but this leads to a cyclic definition, in which the answer leads to another question, which leads back to the previous answer. A far better definition of “dirty art” would be: any piece of art that goes against the norms of the society, and challenges previously accepted beliefs and ideals.

However times change, so do the ideals of a society. Art and messages that were challenging and risque in the 1930s, may seem very simple or commonplace to a modern day viewer. For example, in 1896 a simple 19 second clip of two actors talking and nuzzling, ending with a quick kiss on the cheek was called “hard to bear” and may have been banned in many places. Much later in 1980s Britain, Margaret Thatcher would ban many violent movies in fear that children might watch them. This might seem reasonable but the bans or censorship reached as far as removing and editing around the “ninja-style weapons” in kids’ cartoons such as Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, even removing the word “Ninja” from the title, and replacing it with “Hero,”—which 40 years later is regarded as an unnecessary moral panic. No matter the reality of this undeniable trend of history, many people have attempted to keep a culture locked, static and unchanging. These same people eventually fail though, and the culture changes over time. For instance, one of the most well-known examples of a failed attempt at both controlling culture and running a country is Adolf Hitler.

Hitler’s authoritarian state exercised a tight control on the media and culture of Germany, banning any books, movies, or other works that contained ideas that went against the values of the Third Reich. Infamously, the Nazis participated in massive book burnings, where they would gather books that contained offending material, and disposed of them. Hundreds of thousands of lost novels, diaries, encyclopedias and learning materials would be eviscerated in a matter of hours.

If they couldn’t burn the offending material, they would certainly attack, terrorize, and kill to make sure the undesired material was not shown. They did exactly this with the 1930 film All Quiet On The Western Front.

The film was very critical of war and “presented a realistic and harrowing account of a meaningless war that had led to disillusionment, suffering, death, and ultimately ignominious defeat.” When this anti-war film that “had dared to question Germanic ideals of militarism, honor, valor, and sacrifice for the Fatherland” made it to Nazi Germany, it was met with expected resistance from the government.

The film was being premiered in the Mozartsaal (Mozart Hall). After the premier of the film, the Brownshirts, the Nazi’s paramilitary wing, planned to attack the Mozartsaal hall the day after the premier on December 5th. Brownshirts released white rats, destroyed ticket counters, and released stink bombs and sneezing powder into the crowds of patrons.

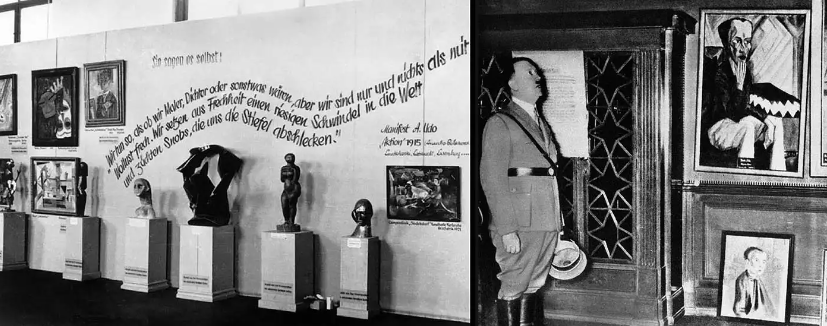

Simultaneously, while the Nazis burned books and attacked the Mozartsaal, they also, counterintuitively, put offending material up for display. The reasoning however is clear: they would simultaneously eradicate, attack, and mock what they viewed as degenerate. The events where they put up the offending material up for display was referred to as “Entartete Kunst” (German for “Degenerate Art”).

These art exhibitions would contain and display modern art of the time, according to Holocaust Encyclopedia, “The Nazis also claimed that the ambiguity of modern art contained Jewish and Communist influences that could ‘endanger public society and order.’ They claimed that modern art conspired to weaken German society with ‘cultural bolshevism’. According to Nazi ideology, only criminal minds could be capable of creating such so-called harmful art.”

The art would be accompanied by many demeaning phrases and slogans painted on the walls, phrases such as “Degradation of the German Woman” and “Deliberate Sabotage of Self Defense.” These exhibitions of filthy and disgusting art would be set up and organized in an intentionally unflattering way—sculptures and graphic works crowded together.

The prices of the artworks would be displayed, although sometimes exaggerated, the message was clear. The Nazis wanted to invite mockery and confusion, ridicule at such high-priced and poorly-made artworks. In fact this is often a common thought of modern day viewers of art, they could see a Jackson Pollock painting and scoff at the notion of “Number 5” costing $140 million dollars, thinking “Millions for those scribbles? I could make that in 2 hours.” Of course, these comments ignore Pollock’s innovations in art and unique “drip technique” and there is a legacy left behind that the viewer does not take into consideration.

Now take these usually small harmless comments, and apply them to the thought process of a militaristic authoritarian regime. Not only did the Nazis hate degenerate art but they also hated degenerate music, jazz in particular. The Nazis also regulated jazz, including the banning of: solos and drum breaks, scat, “Negroid excesses in tempo” and “Jewishly gloomy lyrics.” Originating from America, jazz broke the rigid confines and rules of the past, it was a breath of fresh air, and took a more laissez-faire approach to the structure of music. It originated from blues, and then went on to influence many more genres of music, such as R&B, rock ‘n’ roll, hip-hop and many more to come. This very loose and unique take on music was a threat to the Third Reich, and it was a foreign influence.

Even before the war, America’s influence on the Third Reich was quite evident. In fact, the Nazis took after Jim Crow Laws when deciding how to persecute the Jewish population. After the war, however, the victors and the world as a whole wanted to distance themselves from the ideals, practices and ideologies of the Nazi party.

America still took after Nazi Germany, although very quietly, such as the use of gas chambers as execution before the war, starting in 1924 and still continuing after the war, despite the near inseparable connection between gas chambers and death camps used in the Holocaust, like Auschwitz-Birkenau. Most of the ways America adopts the ideals of facism are more subtle, subdued and are otherwise not immediately threatening. For example, instead of using gas as part of a mass genocide, it was used as a supposed humane method of execution. Instead of forcefully confiscating “degenerate art,” Senator Jesse Helms (R, NC) would argue in 1989, that the “known homosexual” photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, should not receive federal assistance from the National Endowment for the Arts.

And for the standards of 1989, Helms had a point, Mapplethorpe’s art would often be erotic, exploring nude figures of both men and women, and even depicting the BDSM subculture of 1970s New York. Mapplethorpe himself would deem some of his art as “pornographic, with the aim of arousing the viewer, but which could also be regarded as high art.”

However, there is something deeper to Mappletorpe’s photography, something I would love to explore and understand, but am not focused on in this article …

In this specific instance, there are sides to be picked, possible arguments for both Helms and Mapplethorpe, but no matter who comes out on top, the fight over what is morally correct and what isn’t never seems to end. From a small kiss in an early movie in 1896, to Mapplethorpe’s photography and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles in the 1980s, and even video games receiving criticism for their violence, which eventually resulted in a Senate hearing in 1993.

What I find interesting is that those that condemn “filthy” art refuse to analyze it. They cannot grit their teeth and bear the stench of what may at first seem like degenerate art. While it may seem hard to tolerate filthy art, I often find that if you can bear the smell, the art can still provide a worthwhile discussion, whether about the art itself, or the reaction.

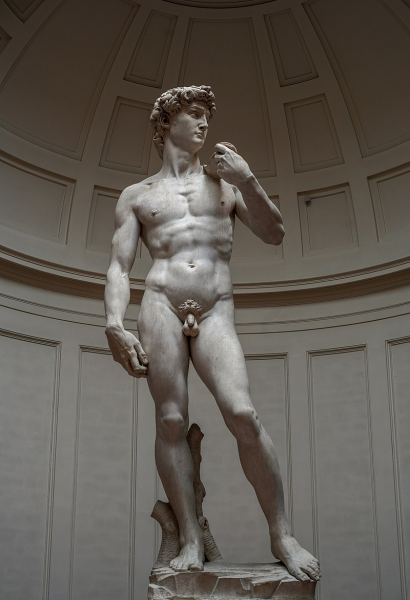

If we return to the idea of analyzing “degenerate art” then what can we learn? What value is hidden within filth? There is not an answer that applies to all pieces of disgusting art, but specifically regarding Mapplethorpe’s erotic photography, why do people praise Greek and Roman statues that have quite visible penises, but then criticize or condemn Mapplethorpe? From this hypocrisy a conversation can emerge, analysis of Mapplethorpe’s work, research can be conducted, and new conclusions can be drawn, all stemming from nude photography. Once you can look beyond the hatred, and understand the art, read between the lines, and maybe do a little digging, then you can learn a lot from filth.

For example, a penis on an album cover can lead to understanding why Taylor Swift re-released her early albums, and how poorly Spotify pays their artists. The backhanded usage of audio from a police officer’s death can inspire empathy and understanding Black Lives Matter. And a drunken, cluttered and messy sounding instrumental can be a launchpad for learning more about minimum wage.

Of course, this is the tip of the iceberg as there are endless pieces of art that have been discarded by society, and an endless amount of hot button issues that art comment on, whether being discussed through the medium of writing, or music, whether the issues are being debated by co-workers in the break room or by Senators on the floor of the Senate.